Real bonuses paid out for fake profits still abound in banking

To paraphrase an old joke from Sir Eddie George, the former Governor of the Bank of England – there are three types of bank shareholders – those who can count and those who can’t. Unfortunately for our pension funds the main thing bank shareholders have had to count since the financial crisis has been the vanishing of our financial wealth.

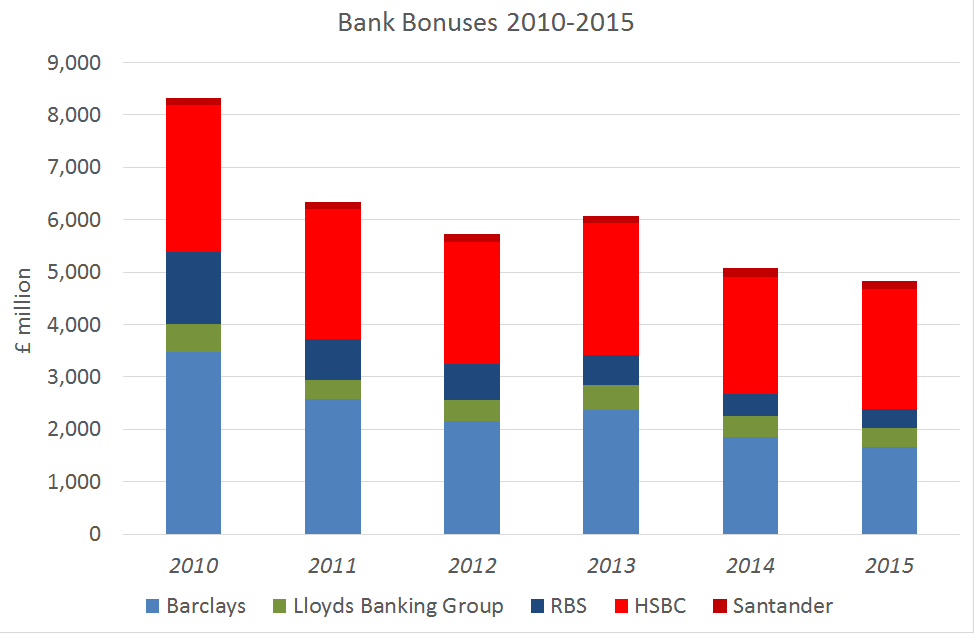

In the long economic boom, banks paid out levels of bonuses based on fictitious profits. Bankers pulled forward profits from the future in the way they accounted for derivatives and profits from products like PPI. They failed to consider the impact of prospective defaults on loans or potential misconduct when paying out annual cash bonuses.

The Parliamentary Commission on Banking Standards concluded that “many of the so-called profits reported by banks in the boom years turned to dust” but “for some individual bankers, they had served their purpose, having been used in calculations leading to huge bonuses which could not be recouped”. New City Agenda found that the UK’s retail banks had paid out £53 billion in misconduct costs, with further costs incurred due to banks’ widespread manipulation of interest rates and foreign exchange markets.

Almost eight years since the financial crisis we are assured by banks and regulators that there has been some progress and the “heads they win, tails we lose” culture is being reformed. But how much has really changed? Since the crisis, banks have chosen to lump the poor quality and risky parts of their business into “non-core” divisions and reported growing profits from their remaining “core” business. They report levels of profit which are “adjusted” to exclude the impact of their past or even present misconduct. “Underlying” profits can also exclude asset sales and the costs of business reorganisation.

Despite being works of fiction, some banks use the level of “core”, “adjusted” or “underlying” profits to determine the level of bonuses. Some might see it as unfair to penalise the current executives for the negative impact of events over which they had no control or responsibility. On the other hand, we don’t see any banks or banking executives adjusting bonuses lower to account for the subsidies provided to them by the ‘Funding for Lending’ and ‘Help to Buy’ schemes. Senior executives are still able to harvest the fruits of taxpayer provided subsidies.

By setting the bonus pool and senior executive bonuses in relation to pre-tax profits, banks have also ensured that shareholders will pay the cost of tax changes such as the corporation tax levy and changes removing the ability of banks to offset misconduct payments against their corporation tax bills.

But what about malus and clawback? Banks are allowed by regulators to exercise any malus by reducing the award of the current year bonus pool – leaving previous bonuses and long-term incentive plans intact. We are told that the bonus pool has been subject to a “collective performance adjustment” but it seems remarkably similar to the previous year. Its a bit like seeing a big sign in a shop window saying ‘70% off’ when a close investigation of the small print tells a different story. Employees and senior executives are still not suffering a real financial penalty for presiding over misconduct. The new rules are not having the intended effect but the PRA and the FCA seem reluctant to intervene.

For presiding over misconduct in the way PPI complaints were dealt with which cost Lloyds shareholders well over £1 billion, the Lloyds Banking Group CEO lost a total of £234,000 of bonuses. This was just 0.7% of his accumulated remuneration of around £33 million over the past 5 years. How do the FCA and PRA expect the threat of clawback to have a significant impact on management behaviour when the levels of clawback are so minuscule?

Investors need to stop bonus levels being determined mainly by pre-tax profits and other “adjusted” or “underlying” measures which exist only in the minds of the executives. It would be a good start for fund managers to vote against the remuneration reports at the bank AGMs – to date, most fund managers have been reluctant to do this. Pay for Chief Executives at the big banks increased by 7.8% in 2015. As Andy Haldane of the Bank of England said in his speech to New City Agenda: “with very few exceptions, no differences were made to executive compensation packages as a result of investor action. And the cases of investors actively voting against pay packages have in any case been rather rare.” Returns for shareholders have been lousy, but most fund managers have been unwilling to stand up to the banks and demand change.

Regulators need to get tough and ensure that reductions in current year bonuses are real and come on top of, not instead of, clawback of bonuses from previous years. We will only see a change of culture when fund managers demand transparent assessments of progress and senior executives feel real financial pain for presiding over misconduct and an aggressive sales based culture. Senior executives need to be rewarded for changing culture, serving customers and society and delivering long-term, sustainable returns for shareholders. Theresa May has proposed that shareholder votes on pay should be binding, but that will only work if fund managers are willing to stand up for our interests as investors. If there is going to be cultural change it has to come from within organisations and be driven by personal accountability and a duty of care.

Lord McFall